Taking stock of President Carter’s robust antitrust record

13 March 2023 00:00 by Claude Marx

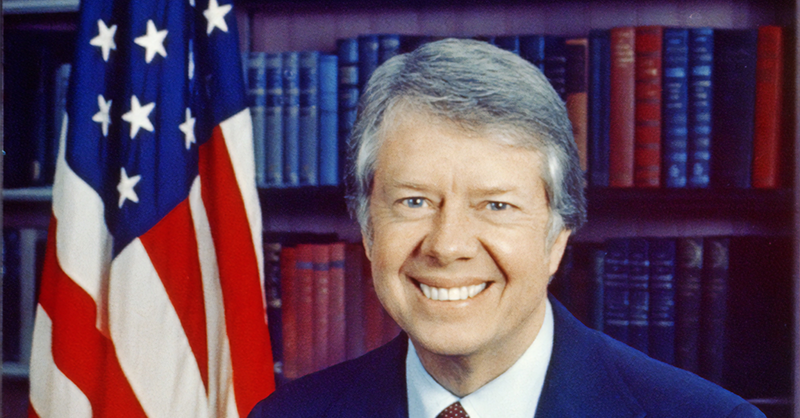

As president, Jimmy Carter made great strides in improving competition through his antitrust policies and by widespread industry deregulation. The 98-year-old recently announced he was entering hospice care, following treatment for several kinds of cancer.

Carter, who served from 1977 to 1981, ran an administration that pursued moderate economic policies and couldn’t be labeled as fully on either the right or left of the political divide.

He’s one of the few presidents to mention antitrust in a major speech. In his 1979 State of the Union address, Carter said one of his objectives was to “fight inflation by improvements and better enforcement of our antitrust laws and by reducing government obstacles to competition in the private sector.”

The Department of Justice’s antitrust division began its leniency program during that time, and this has been regarded as one of the most successful parts of his criminal enforcement toolbox. It guarantees non-prosecution to the first organization or individual to self-report its participation in a criminal conspiracy in violation of Section 1 or 3(a) of the Sherman Act.

Though critics said it let off some criminals, defenders said it has been a net plus for the DOJ over the years.

“It was an investigative tool. It shortcut the process by getting people to come forward in exchange for better treatment. It was an aid to law enforcement,” Sandy Litvack, who was assistant attorney general in 1980 and early 1981, told FTCWatch.

Carter’s antitrust team

Litvack, who succeeded John Shenefield when he was named associate attorney general, had been a trial attorney at the DOJ earlier in his career. Before Carter named him to the top antitrust job, he was a partner at Donovan, Leisure, Newton & Irvine. The firm was founded by William Donovan, who spearheaded the DOJ’s antitrust efforts under President Calvin Coolidge and later launched the predecessor agency to the CIA.

Shenefield had been a partner at Hunton Williams and worked for Lewis Powell, who would be appointed to the Supreme Court and wrote a famous memo for the US Chamber of Commerce urging businesses to increase their political involvement to fight growing anti-corporate sentiment.

While on the high court, Powell wrote his friend Attorney General Griffin Bell urging him to pick Shenefield to run the antitrust division.

The DOJ also brought a rare challenge to a vertical merger. Four film companies — Columbia Pictures, MCA/Universal, Paramount Pictures and Twentieth Century Fox — sought to create a joint company with Getty Oil to form Premiere, a cable network, to rival HBO. The DOJ filed suit in 1980 and the companies called off the deal.

It brought the last criminal case under Section 2 of the Sherman Act until the Biden administration resumed the practice last year. The DOJ sued Braniff Airways and Texas International Airlines for criminal violations of Section 1 and Section 2 for conspiring to exclude a competing airline. Braniff pleaded nolo contender and was fined $100,000, and Texas International pleaded guilty and was fined $100,000.

The antitrust division also managed litigation against two corporate giants, AT&T and IBM, that began under previous administrations. The cases ended during the Reagan administration.

Litvak said Carter’s attorneys general, Bell and Benjamin Civiletti, were insistent that antitrust investigations and cases be shielded from White House influence, especially in light of the interference during the Nixon administration. But Litvak recalled that when his office weighed in on pending legislation, Carter’s legendary attention to detail was quite apparent.

“We contributed to an options memo on a bill and said the administration should oppose it because it would limit the department’s enforcement powers. President Carter wrote on the memo that he disagreed, but then cited the specific law and section in question that already gave us the enforcement power. I was surprised that he didn’t just check the box but took the time to explain his position,” Litvack said.

Under the chairmanship of Michael Pertschuk, during Carter’s term, the Federal Trade Commission caused the most controversy with its consumer protection activities. The FTC prompted lawmakers to deny it funding twice, which forced the agency to briefly close on two different occasions. Still, the agency made strides on the antitrust front.

Pertschuk outlined his agenda in a 1977 speech to the New England Antitrust Conference and stated: “Although efficiency is important, it should not dictate competition policy. Policymakers must sometimes choose between greater efficiency — which may carry the promise of lower prices — and other social objectives, such as the dispersal of power, which may result in marginally higher prices. Economic analysis can clarify the trade-off, but it cannot be allowed to dictate the outcome.”

The agency landed a big win when the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Indiana Federation of Dentists that a conspiracy among dentists to refuse to submit X-rays to dental insurers for use in benefits determinations violated Section 5 of the FTC Act’s ban on unfair methods of competition.

And while Pertschuk, a former top Senate staffer was considered liberal, the runner-up for the post was even more progressive. Bella Abzug, a former Democratic congresswoman from New York who was active on feminist and consumer issues, lost out but as a consolation prize was named chair of the National Women’s Conference.

The Carter administration’s antitrust work came when the field was shifting rightward. During the middle of the term, conservative scholar and former solicitor general Robert Bork published “The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with Itself,” which was a withering critique of what Bork saw as failings of liberal antitrust enforcement policies.

He was a key intellectual architect of the consumer welfare standard, which strongly influenced enforcement strategies during the presidencies of both parties from Ronald Reagan through Donald Trump. The Biden administration has taken a sharp turn away from that approach.

Deregulating sectors

Beyond the antitrust sphere, Carter’s work on competition issues included successfully deregulating certain industries, such as airlines, railroads and trucking. The former small business owner saw those efforts as necessary to change rules that imposed costs, inflation and inefficiencies. He further felt consumers would benefit from lower prices and greater access to air travel.

But the administration required that in exchange for being deregulated, some industries were subject to greater antitrust scrutiny. When Congress passed a bill deregulating the trucking industry, it included a provision removing some of the industry’s antitrust immunity. Specifically, the measure eliminated the immunity that let some trucking companies work together to set certain rates.

A central point person on these matters on Capitol Hill was Senator Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts, Carter’s sometime rival and sometime ally. Kennedy’s top aide on these matters was future Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, who was one of the high court’s experts on regulation and antitrust during his time there.

In 1978, Carter issued Executive Order 12044 requiring all government regulations be subject to a cost benefit analysis and mandating that agencies provide a schedule of when they plan to issue regulations.

He persuaded lawmakers to pass the Paperwork Reduction Act which created the Office of Management and Budget’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA). Agencies must submit proposed rules to the office for review and approval before sending them out for comment.

Former FTC Chairman Bill Kovacic, a junior lawyer at the agency during the Carter administration, told FTCWatch that Carter’s achievements were significant and resonate today, even if they are often unheralded.

“The neo Brandeisians think he went too far and the conservatives didn’t think he went far enough. It shows the perils of being a centrist,” said Kovacic, a Republican named chairman by President George W. Bush.

Related Articles

No results found