Spate of regulatory changes signal it's time to take data privacy seriously in Southeast Asia

27 October 2022 02:33 by Jet Damazo-Santos

After years of incremental developments in Southeast Asia's data-privacy landscape, things now appear to be changing — fast. Over the span of just a few months, the risk of failing to comply with data-protection regulations significantly increased in almost all the region’s major economies.

In June, Thailand's Personal Data Protection Act came into full effect after a two-year delay caused by the pandemic, with administrative penalties of up to 5 million baht ($146,000) and a possible one-year jail term for those who violate it.

By the end of August, companies that breach Philippines’ privacy laws began to be subjected to administrative fines ranging from 0.25 percent to 3 percent of their annual gross income, up to a maximum of 5 million pesos ($85,000).

In September, Indonesia ratified its long-awaited personal data-protection bill, providing for administrative sanctions of up to 2 percent of annual income or revenue and criminal sanctions of up to six years in jail. That act was signed into law by the president last week.

From Oct . 1, violations of Singapore's personal-data protection law began to face substantially higher fines of up to 10 percent of local turnover. That follows a landmark court ruling in September that basically paves the way for individuals to file a lawsuit seeking damages for emotional distress due to a violation of their data-privacy rights.

Also on Oct. 1, a Vietnamese decree requiring local companies to onshore their data went into effect, indicating that other pending decrees on data protection and administrative penalties are not far behind.

Had it not been for the sudden dissolution of parliament in Malaysia, its communications ministry would have also submitted a bill strengthening the country's data-protection law this month.

For companies that haven't been taking data privacy in Southeast Asia too seriously, these changes show it's now time to sit up and pay attention.

"These are not simply paper changes, as the market expectation is these regulators will take effective action against aberrant organizations," Lanx Goh, the global head for privacy at Prudential, told MLex.

Long time coming

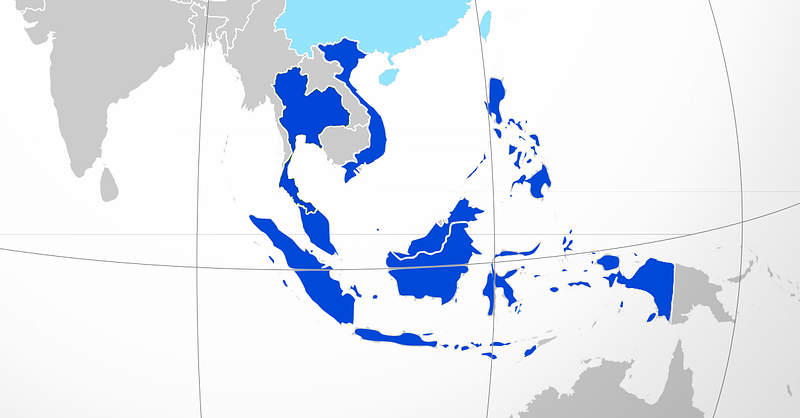

Though it seems that so many changes are suddenly taking place at the same time among members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or Asean, none of these come as a surprise.

"These recent developments in Asean are not surprising as it aligns with the Asean Framework on Personal Data Protection issued in November 2016," said Goh, who used to head the investigations unit at Singapore's Personal Data Protection Commission, or PDPC.

But as in the case of Thailand's enforcement of its 2019 data-protection law, the Covid-19 pandemic created unexpected delays.

Singapore's higher fines were in fact part of amendments to the country's personal-data protection legislation that took effect in February 2021, but the government decided to delay imposing the harsher penalties because of the pandemic.

Vietnam's decree on data localization had been stalled since 2018, Indonesia's data-protection bill was held up for a year over the structure of the privacy regulator, and the Philippine circular on administrative fines took several years because of questions over whether the regulator does have the legal basis to impose such fines.

With economies now recovering from the pandemic, data protection advocates say it's about time Asean regulators get serious about enforcement, especially given the frequency of data breaches around the region.

Global companies that benchmark their compliance programs against the strictest data-privacy regimes in the world — such as the EU's General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, on which many of the Southeast Asian laws are based — perhaps might not have much to worry about. But experts say that’s not the case for a lot of local companies, many of which don't see the risk of non-compliance as outweighing the costs.

Compliance costs

This isn't surprising, because privacy compliance can indeed be expensive. In Singapore, for instance, data-protection officers say a multinational company can easily spend about S$500,000 ($350,000) a year for a good compliance program.

But the PDPC has mostly issued fines below S$100,000, even though it had the power to impose fines of up to $1 million prior to the amendment of the law.

In 2021, for example, Singapore's largest data breach affecting almost 5.9 million individuals only earned Commeasure, the operator of hotel-booking platform RedDoorz, a fine of S$74,000. Despite the scale of the breach, the PDPC said it took into account the company's remedial actions and the impact of the pandemic on the hospitality industry in determining the fine.

In the Philippines, data protection officers can cost anywhere from $500 a month for inexperienced ones for small companies, to as much as $3,000 a month for experienced ones in large firms. But no company has actually ever been fined.

Regulators understand this compliance cost-benefit analysis, which is why, according to Philippine deputy privacy commissioner Leandro Aguirre, they came up with a schedule of fines that would make companies realize that instead of risking both reputational damage and a financial penalty, they could just spend that amount on compliance.

Once Indonesia begins enforcing its new law, companies might find that the risk would outweigh the compliance costs.

"The cost for full [data privacy] gap analysis could be rather high — hundreds of millions to billions of rupiah depending on the size of the company and complexity,” Danny Kobrata, a partner at K&K Advocates and co-founder of the Indonesian Privacy Practitioner Association, told MLex.

A proper gap analysis, he said, would require thoroughly understanding how a company works, how it processes personal data, who collects the personal data for the company, who uses the data, how long it is retained, which parties the data is disclosed to, and more. It would require checking all contracts, forms, and standard operating procedures, and then amending them or possibly creating new ones.

"But the fine of a maximum 2 percent of total revenue is definitely a huge amount. Imagine a large-sized company with revenue of 500 billion rupiah — a 1 percent percent fine would amount to 5 billion rupiah [$320,000],” Kobrata said. "I personally think the compliance program worth the price."

Enforcement roll-out

However, data-privacy advocates say that companies would need to see examples of these changes in actual use, before any meaningful or sustained change in corporate behavior takes place.

But over the coming year, strong enforcement action can only realistically be expected from Singapore’s PDPC and, to a lesser degree, the Philippines’ NPC.

"Singapore and Philippines will be the two likely jurisdictions that will gradually step up on their enforcement effort and increase the financial penalty imposed as they are of more mature regime when it comes to duration of the law," Goh said.

"That being said, it is inconceivable for the enforcement or penalty to escalate drastically and suddenly."

Even the Singapore ruling allowing courts to award damages for emotional distress due to a violation of their data privacy rights is not expected to open a floodgate of private right of action lawsuits.

"This ruling would increase the risk for companies in Singapore as emotional damage is easier to establish than physical damage or monetary loss," explained Goh, whose work was cited by the Singapore Court of Appeal in its ruling.

But he added that proving emotional damage is still “not a walk in the park” and filing lawsuits is not something everyone can afford.

The Philippines' NPC has already said it still has a massive backlog of cases to go through before it can tackle new cases that would fall under the new fines. Thailand’s newly established regulator is still in the process of issuing implementing guidelines, while Indonesia’s new law has a two-year transition period and Vietnam is still waiting for complementary decrees on data protection and administrative fines.

Regulatory impact

So, while all these regulatory changes might make companies sit up and pay attention now, a lack of regulatory action soon would dull their impact.

In Indonesia, for example, law firms are now receiving requests for a data-privacy compliance gap analysis from various kinds of companies, ranging from financial institutions to power companies, largely because the new law has just been passed. Whether they actually go through with costly gap analysis work is another question.

A lawyer for one of Jakarta's top five firms said most companies in Indonesia don’t see privacy as a major compliance risk yet, given how the government has been handling incidents of massive data-privacy breaches.

"They only announce investigations whenever there is a data breach, but nothing really happens after that," the lawyer told MLex on the sidelines of a conference for legal counsels in Jakarta.

The situation is similar to what has been seen in the Philippines so far.

"Whatever buzz was created by the Philippine privacy commission's issuance of its circular on administrative fines in August, that has already subsided," data-protection advocate Jamael Jacob, a former director of the Philippines’ National Privacy Commission, told Mlex.

"And it will stay that way until the first company is fined."

But as Kobrata pointed out, not doing a gap analysis or compliance program early on means the possibility of a data breach in the future is much higher.

This means companies who decide to wait until the first fines are imposed before taking privacy compliance seriously might find that choice to be more costly in the future.

Related Articles

No results found